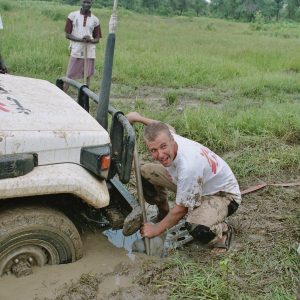

I’m not generally a do-gooder. I love adventure, hands-on work and new experiences for which working in the humanitarian field is an amazing opportunity because you get to see the results of your work immediately. You get to witness how the lives of affected civilians improve, which can be very rewarding. As a humanitarian worker, I am also often in the driver’s seat, acting to effect positive change for individuals and communities. What I do is also very often a lot of fun, and connects me to other people.

What I also love as a humanitarian worker is the high degree of autonomy it involves and being able to act on my own initiative and love being able to improvise and react to unpredictable circumstances. This allows me to rely and act on my own gut feelings and values, which I like. I also appreciate the rather modest legal framework humanitarian work involves and the resulting modest legal responsibility for what I do compared to the approach we have in Switzerland. In other words, I love the freedom of choice in my actions.

But all that I love and describe above has a downside. It implies a measure of loneliness in decision-making. It means the sudden appearance of unpredictable responsibilities and unintended consequences in the wake of humanitarian work.

I have my own experiences of this downside. As a result, I recurrently, I feel guilt for something that happened a long time ago and feel responsible for my own past decisions. Responsible and alone. This is my story.

One of my first humanitarian missions took me to Darfur in 2003/2004. It was at the peak of a period when Sudanese pastoralists were evicting farmers and others from their villages. The pastoralists were being supported by the Sudanese government and entire villages were being burnt down. Mass rape was everywhere. And existing water sources and water wells were deliberately being poisoned by means of dead bodies being thrown into all available water. I could see fear, horror, and desperation in the eyes of people who told me stories which were so saddening that I stopped believing in the goodness of mankind. I remember in particular the story of a man, who had to watch as insurgents opened up the belly of his pregnant wife – alive – and killed the twins she was expecting. I saw tens of thousands of internally displaced civilians seeking refuge from being killed and being humiliated to an extent which is far beyond imagination. During my stay, we also heard of ongoing mass executions and I saw people who were driven crazy by their traumatic past – shouting non-verbal rants in public – eyes wide open. Myself, I had to deal with decision makers who were in favour of the evictions, oppression, rape, and killings. They wanted to get rid of the refugees and I had to negotiate with them for ways to make the lives of the refugees at least in part supportable.

I remember, I mainly lived in a house in the middle of a refugee camp. Together with a team of six people. Twenty four hours a day we could hear children crying. Refugees had their tents attached to the walls of our rather small compound. They felt safer when we were present because they knew we would advocate for what happens. Life at that time meant extreme poverty for the refugees and host communities. Never ending work for us few humanitarian workers. The region was on the brink of a Cholera outbreak, measles epidemic ongoing, people sick of contagious Hepatitis-E. Exotic illnesses such as Elephantiasis and intestinal worms of which I don’t even remember the names.

I was responsible for water supply, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) at the triangle within Sudan to the border with Chad and the Central African Republic. I volunteered for MsF, Doctors without Borders. One of my tasks was to help with the construction of hand dug wells.

The construction of a hand dug well is a lot of fun, a lot of manual work, very rewarding, and one finished and operational well provides water for around 1000 persons. I mainly worked with local constructors, as they know the region and also have a tremendous experience where you find water and how to do the work in detail. I remember in particular Ali. He was an older local constructor, around 70 years old. He didn’t speak a single word of English, so I had Yehya with me all day who translated every word. Ali had a lot of experience with the construction of such wells. He knew exactly which place was good to find water and where the soil was easiest to dig. We were choosing several places together where we built hand dug wells and put them in operation. I think we really liked each other and despite his old age he was climbing up and down inside the well like a twenty year old guy. Moreover, when Ali was present, he was always bringing a good mood to the site. He was respected by everyone.

I don’t remember exactly on how many wells I helped building. I mainly worked with Ali. There were several and I remember in particular one well in Um Dukhun (أم دخن) which was extremely deep. Usually a hand dug well is just a couple of meters deep. Once the water well is in operation, you’ll need a bucket fixed at the end of a rope to be able to reach the water table and pull it up again when it’s full. This particular water well which I built with Ali was almost 20 meters deep. This corresponds the height of two stacked family-houses in Switzerland. Of course we were taking care when constructing. Even though the prospects of reaching the water table were not extremely good, we managed to reach water. I remember how Ali was climbing up and down the well. He was concerned. Because this well in Um Dukhun was too deep to be easily used, as you needed a very long rope to reach the water table with your bucket. Also the yield was so-so, that’s why it was so deep. Construction was definitely not easy because the soil was extremely hard and digging by hand was a challenge. Building that well took a lot of time.

Eventually I left Sudan and went back to Switzerland when this particular deep well was not yet completely finished. But of course, after some time, I was curious to know how they finished the work and how the water well was operating. I remember, I asked Yehya, who was my translator at the time.

Yehya told me the sad story of a child who fell into the well and couldn’t be saved anymore. Not very long after I left. What happened exactly? Was there no wall around the hole? Did they really finish the works or ended it up in an eternal unfinished site? Did the child start to climb around the water well? I will never know. But was it my fault? Was it even a mistake to start the construction of that well as success was not sure? I remember, when Yehya told me the story on the phone or even by text message, I had a lot of open questions but maybe we ended up talking about something else or we lost touch.

In the meantime I forgot a bit about this story. However, it was always present in my head and recurrently it’s coming back.

Just very recently I was asked to tell a story of my past as aid worker. The well in Um Dukhun came to my mind. Ali; the construction work; the rather modest success. The child who died.

Thinking about this story bugs me recurrently. Thinking about it this time makes me feel like crying. Could I have prevented that accident? What happened exactly? I will never know. I imagine the grief of the mother who might be still alive today. Did she have other children? Probably, but what would this child, who died, be today? After almost twenty years? Was I just unexperienced or could I have done a better design? Is it my fault? Was it collateral damage of my work in a context of unprecedented suffering? What does this death mean in the context of the ongoing conflict, killing, and suffering?

Most likely I will never find an answer to my open questions. From a legal perspective no one will ever sentence me or find me guilty. It’s my own moral values which decide on how I cope with that.

This story teaches me in a very unpleasant way, that legal aspects and rules are much less important than my own moral values. And my own moral values depend on the current situation I’m facing. Maybe that’s why the legal framework in humanitarian work is rather modest. I bear the responsibility for my own actions. As humanitarian worker you might have a lot of autonomy and freedom. But you are also confronted with some kind of loneliness regarding your decisions and loneliness in bearing the consequences of your own actions.

What happened cannot be undone.

The death of a child. Could I have avoided it? What if I was still there? What does it mean in the context of what was going on in Darfur at the time? Would I be found legally guilty if the same happened in Switzerland? Will I remain feeling guilt based on my own values?

2 thoughts on “Irreversible Actions – Memories from Darfur”

Well Lucas hope you still looking as handsome now yep I often think of us and the terrible situation

However we did our best and worked with the population. Have a glass of

Wine for me

Thanks for the water for the clinics could not have done anything without it ❤️

Whow, Joanie!! What a nice surprise! Thanks for your comment, and yes, we did our best! I’m even having two glasses of wine for you! ❤️

Comments are closed.